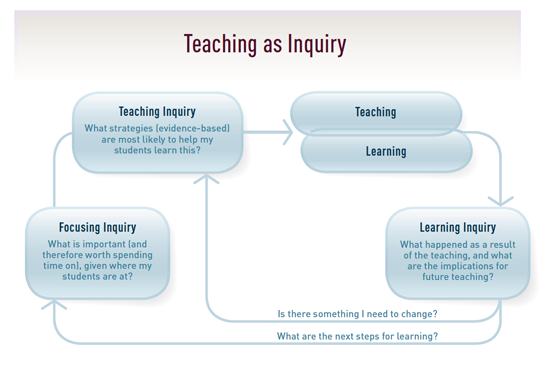

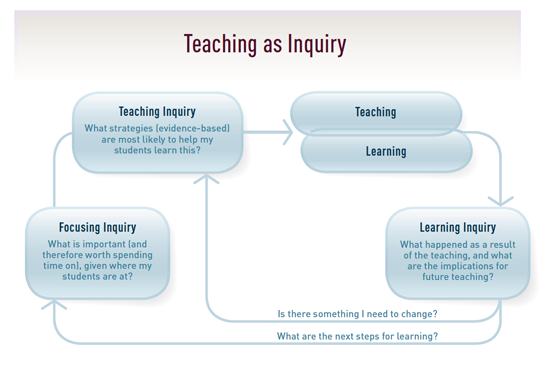

The teaching as inquiry model

The cycle of action and reflection is a dynamic process that unites theory and practice. It is critical to most learning and teaching situations in the arts.

Teachers ask questions and reflect on their teaching.

Teaching as inquiry is a cyclical process based on gathered evidence of how teaching impacts on student progress.

In the arts we can use the teaching as inquiry model to improve learner outcomes.

Learn more:

NZC_Teaching as inquiry diagram

If you cannot view or read this diagram, select this link to open a text version.

Questions to consider

Before (focusing inquiry)

- What do I know about each student’s prior knowledge, goals, and aspirations, and learning strengths and needs?

- What is important and worth spending time on?

- What concepts or vocabulary need to be introduced or reinforced?

- What learning contexts might help the student explore these areas?

During (teaching inquiry)

- How can I teach my next lesson most effectively?

- What learning tasks and approaches are most likely to help this student to progress?

- What informal (formative) assessment methods can I use to monitor this student’s progress and understanding?

- Do I engage this student with the learning context effectively?

- Do I recognise and accommodate the unique learning needs of this student?

- Do I incorporate tikanga Māori into my teaching?

- How can I involve families, community, and whānau in my teaching?

After (learning inquiry)

- What happened as a result of the teaching?

- Did this student achieve the specified outcomes?

- What are the implications for future teaching?

You would then pose a question from the 'before' section to commence the next round of inquiry.

TOP

Using the model: A snapshot in dance

Dance teachers regularly apply the teaching as inquiry model to teaching and learning in their classroom. In choreography, for example, where students at level 6 would need to complete several tasks throughout a year’s programme, teachers can develop ways of raising students’ engagement or application or invention across several tasks in order to raise achievement overall.

Teacher A’s example

Focusing inquiry: Given where my student is at, what is important and worth spending time on?

“I have a student [who we will call Lucy] who recently presented a short piece of choreography that was approximately 60 seconds in length.

The student is highly capable in performance and is an accomplished studio dancer outside of school.

While the choreography did meet the expectations of the task, I wondered why the quality of the choreography and its composition did not match her excellent execution of the movement.

I need to help Lucy to move away from the generic movement vocabularies that her studio involvement fosters in her and develop her ability to think outside the square when she develops original movement for the next choreography task.”

Teaching inquiry: What strategies are mostly likely to help my student reach this goal?

“Lucy is a high-achieving dance student, who often gains Excellence in performance assessments. However, I want to ensure she matches her excellent performance with equally high standards of choreography.

I began by asking her to re-perform the dance sequence that led me to form this inquiry.

While Lucy did this, I asked her to repeat parts of it several times, each time asking her to alter or change an aspect of the original sequence (for example: the level a move was performed at; the body base used; the limb used to perform the movement; the timing of the movement; the facing of her body in the space; the pathway she took etc).

I then asked her to take some time alone to rework the sequence completely. Lucy became quite excited by the new-found, ‘unusual’ way of moving [that] this approach armed her with. I advised her to keep such ideas in mind when preparing for the next choreography task.”

Learning inquiry: What happened as a result of my original inquiry aim or goal and the strategies developed? What are the implications of this for future teaching?

Teacher A was keen to see if the strategies used with Lucy would bear fruit in the next assessment. She noticed (as soon as Lucy was introduced to the task) that “she now naturally approaches the first step by using and altering the elements of dance rather than by using generic/known steps which she previously would change just enough to fit the current task stimuli”.

Teacher A says that she now scaffolds choreography tasks for all students in a similar way to the strategies she tried with Lucy and has noticed that other students’ movements have become increasingly more effective and imaginative as a result.

TOP

Using the model: A snapshot in art history

The model is a cycle of inquiry based on evidence, including student voice, which constantly evaluates and moves forward.

Focusing inquiry

What do my students still need to learn once the course material has been taught?

By the middle of term 3, the teacher remains concerned that, although some skills have been learned, retention of information or perhaps how to group, sort, or apply information within different contexts is not clear to individual students.

Student responses to plate (images) questions produced tentative answers or void responses from a significant number of the class.

The teacher looks for strategies to increase student ability to evaluate and apply principles of analysis to new plates.

Teaching inquiry

How can I change my lessons so that my students apply skills of analysis to new contexts?

The teacher decides that the breadth of knowledge is overwhelming and the students are struggling to understand the mechanisms of applying principles of analysis.

The teacher decides that clarity about what is essential knowledge will create confidence in her students. What is it that students need to know? What skills are students still not demonstrating?How do I know this?

The teacher writes the learning intention for each lesson on the board and has a topical learning question to answer at the end of the lesson.

Asking questions that require an opinion and students to choose a position, for example, Is Rauschenberg or Warhol more original or important or controversial? helps to spark debate or engagement.

The teacher knows that students are more confident trialling their answer in pairs before answering to the whole class.

Learning inquiry

What happened with these strategies? Was there evidence of reaching my original goal and inquiry?

If the class becomes more interactive and confident, if students are willing to try answers and even be wrong, both students and teacher have a clearer picture of where and how learning is occurring.

The teacher introduces scaffold platforms or structures that define and limit the content that needs to be learned and allow time for students to try new questions in class.

The teacher allows the student to sort out the important things to remember or learn by:

- creating a template for student use (each lesson limits the material covered to say two art works per artist and three points for iconography or style characteristics for each artist or style)

- using mnemonics, or memory games

- making datashow presentations with a consistent structure and summarised information.

< Back to pedagogy

Last updated August 14, 2019

TOP