Points of view, values, and perspectives in senior social studies

Exploring values and perspectives is a key aspect of the social inquiry approach in social studies. It is closely linked to considering people’s responses and actions, and relies on a rigorous understanding of the historical, contemporary, and contextual information about a social issue. Exploring values and perspectives has been identified as a challenging aspect of teaching social studies due to the contested nature of many social issues. However, in the absence of exploring values and perspectives in social studies, students will have a limited ability to participate as citizens in a complex and conflict-ridden society.

Why study points of view, values, and perspectives in (senior) social studies?

In senior social studies we use points of view, values, and perspectives to distinguish between ways in which people and groups ‘see’ the world. This enables us to explore and explain people’s thoughts and actions as part of their participation within society and to examine how these inform their responses to and decisions about social issues.

What are points of view, values, and perspectives?

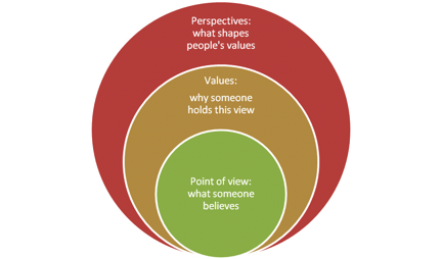

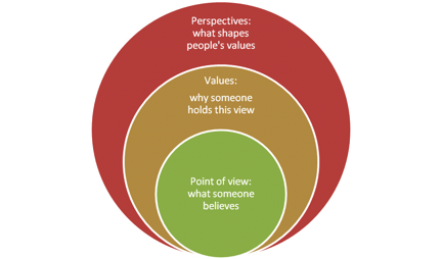

It is perhaps helpful to view points of view, values, and perspectives as a nested set of beliefs held by individuals/groups. At the first level, we can see the points of view people/groups hold, which are often framed as “I think that…” Frequently this point of view is shaped by a person/groups’ values which explain more about the underpinning beliefs. Values in turn are often informed by a perspective or world view which represents a set of ideas which can be explored across groups in society – for example a particular religious, cultural or political perspective.

The following diagram summarises these levels of understanding:

Perspectives diagram

Source: Derived from Keown, 2005

If you are unable to view this diagram a text version is available.

Points of view

People’s points of view may be expressed in their words or actions. Other words for ‘point of view’ are viewpoint, opinion, position, preference, or a stance taken in regard to an issue or proposal.

An example of a point of view is “I’m all for the City Council introducing e-waste recycling – I’m worried about the state of our local landfill”.

Values

The New Zealand Curriculum states that values are deeply held beliefs about what is important or desirable (Ministry of Education, 2007, p.10). There are different kinds of values, such as moral, social, cultural, aesthetic, economic, and environmental values. Understanding people’s values can help to explain why people hold a particular point of view.

For example, someone might support e-waste recycling because they believe that the environment needs to be protected to safeguard the future of the planet or because they believe in kaitiakitanga – the guardianship of a resource for future generations.

Perspectives

In senior social studies students develop their understanding of how people’s points of view and values are shaped by a complex and intersecting landscape of perspectives. Other words for this are worldviews, ways of looking at the world, lenses, paradigms, ideologies, and theoretical frameworks.

For example, someone who is concerned about e-waste recycling and the environment might be coming from an ecological or Deep Green perspective. From this perspective, the environment has an intrinsic worth independent of its monetary value or ability to be used. Another perspective could be a social justice or critical theoretical perspective. A person or group who is informed by this perspective is concerned about how people of different ages, ethnicities and socio-economic groups are able to access or benefit from recycling or environmental initiatives, and how these may impact on the well-being of all groups, especially the marginal.

Particular bodies of thought or sets of organised ideas provide us with perspectives. These are not any one person’s views but an aggregate of ideas that has been built up over decades or even centuries. Political ideologies are a great example of this, reflected in party policies that are put forward for others to agree/disagree with.

At some point in time, it is possible to see that a particular set of ideas tends to always take us in a particular direction, tends to always build on the same foundational ideas and tends to require us to think in particular kinds of ways. Once a knowledge framework has developed this kind of stature, scientists and social scientists tend to talk about the framework as a ‘theoretical perspective’.

It is important to note that perspectives are umbrella terms that encompass a wide variety of values and points of view. There is, for example, no one single environmental, Māori, or feminist perspective. Instead, an exploration of perspectives tends to provide insights into how a group of people at a particular time and place feel and act about a social issue – but this does not mean that this will apply across the whole group and across all time periods. It is the complexity and fluidity of people’s responses that we want students to understand rather than static impression of how people and groups operate in society.

How does understanding perspectives link to the New Zealand Curriculum?

Understanding perspectives is strongly linked to the thinking and participating key competencies, values statement, and social inquiry methodology outlined in the

New Zealand Curriculum. Understanding different perspectives encourages greater diversity in the approaches to, and representation of, the knowledge, values, and attitudes to which students are exposed. It further gives students the capacity to critique taken-for-granted ways of understanding the world.

Different perspectives enable students to “challenge the basis of assumptions and perceptions” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 12). For example, when they are finding out information about sustainability, they may come to understand that the concept is understood differently within various theoretical frameworks and over time.

Understanding perspectives also enables students to “critically analyse values and actions based on them” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p.10). When considering responses and decisions, students can use perspectives as a tool for thinking about how values and beliefs inform actions, as well as providing a way to explore alternative social actions and evaluating their effectiveness.

How are values and perspectives linked to actions and responses?

One of the goals of exploring people’s values and perspectives is to see how these may shape their responses and actions. In turn, many people’s actions reflect their values. For this reason, it is often important to explore values and actions together rather than separately.

The following example shows how perspectives can be linked to actions: Many people who participated in

eDay value the environment in some way. For example, they may be concerned about impact that e-waste (containing plastics, lead, cadmium, and mercury) can have on the environment, wildlife, and human health. However, people have different perspectives about what should happen in the future. From a technocratic perspective, many believe that technology will ultimately solve the problem through, for example, the development of biodegradable products. Others who hold a deep ecological perspective argue that we really need to learn to consume less, and see eDays as being effective only in the short term.

What perspectives are valid?

It would be impossible to list all perspectives that could be used in social studies. Perspectives need to be broad, open, and wide ranging, not narrow and inflexible (Keown, 2005). Within a social studies context, a range of perspectives can be explored. For example, in the course of a study of globalisation, the following perspectives could be covered:

- Ecological perspectives (globalisation comes at a cost to the ecosphere)

- Pacific cultural perspectives (question the place of Pacific identities within the globalised ‘mass’)

- Political perspectives ( for example, right/left-wing; green politics; democratic perspectives)

- Neo-liberal perspectives (stress the importance of the free market, individual choice)

- Feminist perspectives (question who globalisation serves)

- Libertarian perspectives (globalisation improves freedom and wealth for all)

- Post-colonial perspectives (globalisation as a new colonising force)

- Pro-globalist perspectives (the first phase of globalization, which was market-oriented, should be followed by a phase of building global political institutions)

- Anti-globalisation movements’ perspectives (poorer countries are disadvantaged, exploitation, weakening of labour unions, low wages/high turnover)

As students gain deeper understandings of perspectives in social studies they will understand that people and groups can hold multiple perspectives. For example, a New Zealand exporter could hold a pro-globalist perspective whilst simultaneously raising concerns about the environmental impacts of trade from an ecological perspective.

Useful references

Chalmers, L., Keown, P. & Kent, A (2002). Exploring different ‘perspectives’ in secondary geography: Professional development options. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education. 11(4), pp313-324

Keown, P. (2005). Perspectives in the social sciences. Paper presented at SocCon, 2005, Wellington (Sept 25-28, 2005)

Ministry of Education (2008). Approaches to social inquiry. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2009). Being part of global communities. Wellington: Learning Media. (especially pages 9, 13, 38)

Last updated May 5, 2021

TOP